Catherine Waller

October 9, 2025

I have always been fascinated by the fall of empires. How can such large organisations, with seemingly infinite power and resources, collapse into ruins? History shows that dominance often breeds complacency. Structures designed to maintain power in one era can become rigid, inefficient, and unable to respond to new realities. Whether in nations, militaries, or corporations, the seeds of decline are often sown long before the moment of visible failure –hidden in the inability to adapt when the world inevitably changes.

In episode6 of my favourite podcast, Cautionary Tales, award-winning economist and journalist Tim Harford explains how some of the greatest missed opportunities in history were not the result of a failure to invent, but a failure to adapt.During the First World War, British strategist J.F.C. Fuller recognised thatthe newly developed tank could break the deadly stalemate of trench warfare. Britain had the best tanks, a clear strategic vision, and the world’s leading mechanised forces – yet it failed to capitalise. Why? Not because the army didn’t see the potential, but because it was unable, or unwilling, to restructure itself around a radically different way of fighting. In contrast, Hitler’s newly rebuilt military – unburdened by bureaucracy and tradition – was able to design its organisation from the ground up around the tank, unleashing the devastating strategy of blitzkrieg. This story has repeated itself time and again: Kodak with the digital camera, Xerox with the graphical interface, IBM with the PCr evolution. These companies saw the future clearly, often before theircompetitors, but each was trapped by the weight of its own legacy. Today, as Apple, Microsoft, and Google aggressively incorporate AI into their existing platforms, the question looms large: are today's tech giants about to stumble in exactly the same way?

Throughout history, some of the most successful companies were not destroyed by external competition, but by their own inability to adapt to the very innovations they helped create. Kodak, Xerox, and IBM each saw the future with astonishing clarity. Yet each failed –not because they lacked vision, but because their internal structures, incentives, and cultures were unable to embrace the organisational changes required.

In their 1990 paper, Architectural Innovation: The Reconfiguration of Existing Product Technologies and the Failure of Established Firms, Henderson and Clark argue that established companies often fail not because they lack innovation, but because they struggle to adapt when subtle changes in how components are integrated – so-called architectural innovations – render their deeply embedded organizational knowledge obsolete. They distinguish between three types of innovation:

Architectural innovation is especially dangerous for established companies because it’s subtle: it keeps much of what the firm already knows, while quietly undermining the value of its organisational structure. Since this kind of knowledge is built into a company’s communication, routines, and decision-making, leaders often underestimate how disruptive these changes can be. By the time they realise the scale of the threat, their position is often already weakened – not because they lack expertise, but because they are stuck in systems designed for a world that no longer exists.

To understand how even the most dominant organisations can fall victim to these hidden shifts, it is worth revisiting the cautionary tales of Kodak, Xerox, and IBM.

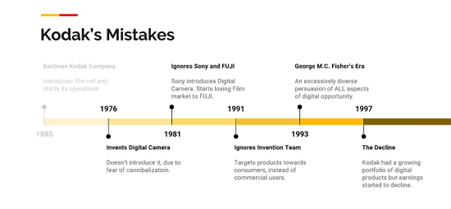

In 1975, Kodak engineer Steven Sasson invented the world’s first digital camera – a crude prototype by today’s standards, but a glimpse of photography’s future. Kodak’s leadership recognised its potential early on but feared it would cannibalise their highly profitable film business. Rather than lead the transition, they suppressed the innovation – a decision driven by a structure optimised to maximise film sales, not foster disruption. At its peak in 1996,Kodak commanded over 90% of the U.S. film market and was valued at more than$31 billion. Yet by 2012, Kodak filed for Chapter 11 bankruptcy, its market value having declined by over 99%. As Henderson and Clark’s framework predicts, Kodak’s failure was not a lack of vision, but a failure to overcome deep-rooted organisational inertia. By the time competitors like Sony and Canon moved aggressively into digital photography, Kodak was too structurally rigid to respond – and the company that once defined an industry faded into irrelevance.

Similarly, Xerox’s Palo Alto Research Center (PARC) developed groundbreaking technologies in the 1970s – the graphical user interface (GUI), Ethernet networking, and the laser printer – that would underpin the personal computing revolution. But unlike Kodak, Xerox’s failure wasn’t rooted in fear of cannibalisation; it was a failure of strategic alignment. PARC was a research powerhouse, yet Xerox’s core business – selling copiers to enterprises – had no natural bridge to consumer technology. Lacking commercial pathways and organisational champions to turn inventions into products, Xerox allowed companies like Apple and Microsoft to build empires atop its breakthroughs. Despite ranking among the S&P 500’s top 10 in the early 1970s, Xerox’s valuation collapsed by over 90% by the early 2000s, reduced largely to a printing services firm rather than a tech pioneer.

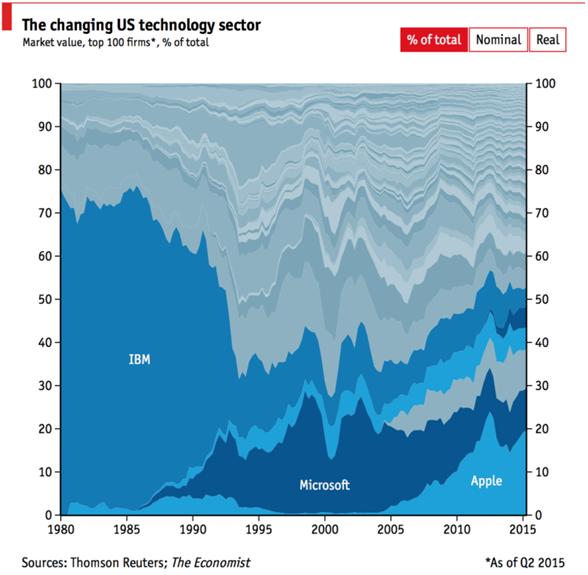

IBM's story illustrates a different risk: losing control of a new ecosystem. In 1981, IBM introduced the first broadly successful personal computer – a landmark that helped define the modern computing era. Yet IBM, seeking to protect its mainframe business, outsourced the PC’s operating system to Microsoft and its processor to Intel. In doing so, it ceded control over the two most critical layers of the new ecosystem. For 17 years, "Big Blue" was the world’s most valuable company, but by 2005, it had exited the PC business entirely, and by 2020, it was removed from the Dow Jones Industrial Average – a slow erosion driven not by a lack of vision, but by strategic missteps in ownership and control.

Artificial intelligence today straddles the line between incremental and architectural innovation. For incumbents, AI enhancements have largely been incremental –bolted onto existing platforms without rethinking underlying structures. Yet true disruption lies ahead: AI could reconfigure the linkages between files, tasks, and interactions so profoundly that legacy systems become liabilities. Over time, it may even catalyse radical innovation, giving rise to entirely new computing paradigms that render today's architectures obsolete.

Just as Kodak, Xerox, and IBM failed from a lack of adaptability, today’s tech giants risk repeating the pattern. For investors, understanding whether these companies can rewire their foundations –rather than simply iterate – will be critical in assessing whether their dominant positions are sustainable in the AI age. Apple, Microsoft, and Google have eagerly embraced AI, yet instead of rebuilding their foundations, they are layering new technologies onto systems designed for a different era. It is a striking irony that the very companies who once disrupted old industries must now confront the same structural challenges they once exploited.

Apple's experience with Siri exemplifies the challenge. Launched in 2011, Siri was pitched as a revolution in human-device interaction. Users were promised a virtual assistant that could book restaurant reservations, intelligently navigate to physical places, remember user preferences, and grow smarter over time. In its early years, Siri was ahead of its time – it was not only the first true AI voice assistant on a smartphone, but also the best. Yet despite its early promise, Siri has failed to keep pace with rising expectations, and its competitors. In independent testing by Loup Ventures in 2023, Siri correctly answered approximately 83% of queries, compared to 93% for Google Assistant. In everyday use, Siri often falls short of even basic expectations – half the time, it fails to understand simple requests, and when it does, it frequently misfires – playing a playlist instead of a song or locating the correct restaurant chain but in the wrong city.

Siri’s persistent limitations are not due to a lack of effort or investment, but stem from deep architectural constraints. Originally, Siri was built as a command-and-control system: it recognised pre-programmed words and phrases and responded with pre-programmed outputs. This worked well in the early days, when expectations were modest. As the field of artificial intelligence evolved, Apple attempted to retrofit Siri with more modern techniques – adding layers of machine learning to improve voice recognition, context awareness, and recommendation capabilities. However, the foundational structure remained brittle: a patchwork of hard-coded responses layered with increasingly complex "middleware," rather thana system built from first principles to learn and adapt dynamically.

The arrival of large language models(LLMs) like OpenAI’s ChatGPT in 2022 marked another seismic shift. LLMs demonstrated that conversational intelligence could be fluid, contextual, and genuinely adaptive – characteristics that Siri, shackled by its legacy architecture, struggled to emulate. Even with the launch of Apple Intelligence in 2024, many of Siri’s underlying issues persist. Rather than rebuilding the assistant from the ground up to harness the power of modern AI architectures, Apple opted once again for incremental improvements bolted onto ageing infrastructure. The result is a system that feels increasingly out of step with user expectations and with the capabilities demonstrated by AI-native competitors. Siri’s journey illustrates a broader risk facing today's tech giants: it is not enough to add new technologies on top of old structures. True transformation demands rethinking, and rebuilding, from the architectural level up. Microsoft's experience with Copilot shows a similar pattern: despite its promise, Copilot remains constrained by legacy application structures and ingrained workflows, with less than 15% of eligible Office users actively engaging within the first six months.

Google’s challenge runs even deeper. Despite world-class AI research, its core infrastructure – built over decades to index, rank, and monetise information – is deeply tied to advertising. Over80% of Google's revenue still comes from ads, a model dependent on static search behaviour. Integrating AI-powered answers directly into Search risks cannibalising that revenue. Google’s search advertising business relies on selling keywords to advertisers so that they can more effectively target potential customers. However, AI summarised responses reduce the need for users to click on links, which could lower ad impressions and undermine the relevance of sponsored results.

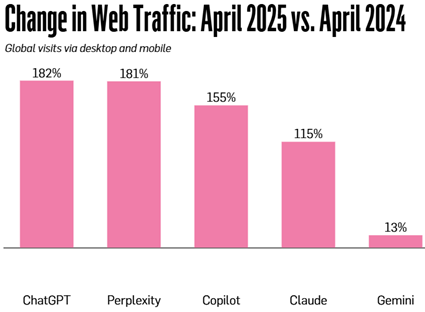

This is already starting to show in hard data. In April, Google’s global search traffic declined 1% year-on-year, while traffic to upstarts like ChatGPT and Perplexity surged by more than 180%.On Apple’s Safari browser, searches through Google dropped for the first time in history. According to digital intelligence company Similar web, nearly 77% of U.S. Google searches that return an AI Overview result in zero clicks, and a recent analysis by Ahrefs found a 34.5% decline in average clickthrough rate when AI Overviews are present – suggesting real pressure on Google’s monetisation engine.2

Internally, Google operates with a “dual brain”: one side pushing toward an AI-native future, the other defending its cash cow. Leaked internal memos show senior leaders openly grappling with this tension, acknowledging that it’s better to lose traffic to Gemini, Google’s own AI model, than to rivals like ChatGPT. And yet, Google is far from passive. It has aggressively rolled out AI Overviews and launched AI Mode – a search experience designed for complex, multi-step queries. Early data suggests these tools are boosting engagement in key markets like the U.S. and India. At the same time, Google is experimenting with new native ad formats for AI-generated answers, betting that more contextual ads will offset declines in traditional keyword revenue.

Like Kodak’s attachment to film, Google’s economic model may prove harder to rewire than its technology stack. But unlike Kodak, Google is moving fast, with the scale, talent, and infrastructure to shape its own disruption – if it can overcome the inertia of past success.

Today’s AI landscape remains largely fragmented. While many tools are powerful in isolation, they operate in silos: one application generates images, another assists with coding, another drafts documents. Users must manually stitch these tools together across disconnected platforms, losing context and efficiency at every step. Meanwhile, a new generation of startups is emerging to exploit these weaknesses. Unencumbered by the need to protect old revenue streams, legacy workflows, or entrenched customer expectations, they have the freedom to rethink foundational assumptions – and in doing so, they offer a glimpse into what the future of technology could look like. These emerging players may also represent the next frontier of investable opportunity – not because they have the loudest demos, but because they are structurally designed to succeed where others must retrofit.

Over the weekend, I had the pleasure of connecting with an old friend who gave me the inspiration to write this research note. He was telling me about his new startup, which is developing a web-based operating system (OS) built entirely around AI integration. Unlike traditional operating systems, which treat files, applications, and workflows as discrete and largely static entities, this AI-native OS treats information as dynamic, interconnected, and constantly evolving. Users can generate documents, presentations, and spreadsheets simply by describing their goals in natural language prompts. The system can seamlessly pull from every file, project, and data source within the environment, as well as connect to 3rd party programs like social media through APIs, offering a level of integration that feels intuitive rather than mechanical. What surprised me most, is that beyond content creation, the operating system itself is self-organizing and self-correcting. Files are automatically categorized, linked, and updated across applications. Minor issues that would typically require human intervention – such as broken links, outdated files, or inconsistent document versions – are identified and resolved in the background. In effect, the system acts as its own IT administrator, dramatically reducing the need for traditional technical maintenance. It’s not just like stepping into a self-cleaning library; it’s more like living inside a self-evolving city – where the streets rearrange themselves to clear your path, the bridges rebuild to speed your journey, and new structures rise just as you realise you need them. This frees users to focus on higher-value tasks while the AI ensures the environment remains coherent, efficient, and up to date.

This vision remains rare among incumbents. According to McKinsey’s 2025 State of AI survey, only 21% of companies using AI have amended their operational architecture to accommodate the new technology. Fewer than one-third have built performance tracking metrics for AI initiatives across their business. Even among large enterprises, just 28% report CEO-level oversight of AI governance – a critical gap when architectural transformation demands leadership alignment, not isolated departmental experimentation. At the same time, the economic stakes for those who move boldly are rising sharply. McKinsey estimates that generative AI could contribute between $2.6 trillion and $4.4 trillion annually to the global economy, with the greatest potential value concentrated in customer operations, marketing, software engineering, and R&D. Despite this opportunity, much of the value remains unrealised due to fragmented, surface-level deployments.

For long-term investors, the message here is not to abandon high-quality tech holdings – it is to understand where the next leg of value creation may come from, and where risks to incumbents might emerge. Companies like Apple, Microsoft, and Alphabet are still global leaders with vast resources, world-class talent, and entrenched user ecosystems. Their recent moves – including Apple’s collaboration with OpenAI, Microsoft’s investment in OpenAI and AI integration across Azure, and Alphabet’s Gemini and DeepMind initiatives – demonstrate serious intent to lead in AI.

However, history shows that innovation risk often stems not from a lack of technology, but from the difficulty of adapting existing business models and structures. Investors should pay close attention to how these firms integrate AI into core workflows, rather than just product demos or feature updates. For example, is Alphabet evolving its advertising and search model to reflect generative AI’s potential to bypass traditional queries? Is Microsoft reshaping Office into a context-aware AI workspace, rather than a collection of legacy apps?

This doesn't mean investors should rush to sell their existing holdings in big tech. Instead, it highlights the value of diversification – not just across geographies or sectors, but across paradigms. Allocating a portion of capital to smaller, AI-native businesses (through venture, thematic ETFs, or specialist funds) can complement core holdings and ensure exposure to the architectural shifts reshaping the tech landscape. For existing shareholders of Apple, Microsoft, Alphabet, or other tech giants, the goal is to remain watchful, not fearful – these firms may yet lead the next wave, but they will need to do so on unfamiliar terrain.

The history of innovation is rich with examples of organisations that glimpsed the future but failed to realign themselves to seize it. Kodak, Xerox, and IBM all faltered because they could not reorganise their structures fast enough to match the potential of their own inventions.

As Tim Harford recounts in Cautionary Tales, even organisations that recognise and develop ground-breaking technology, like the British Army with the tank, can squander their advantage if they fail to reorganise themselves around it. Today’s tech giants, Apple, Microsoft, and Google, now stand at the same crossroads they once forced others to confront. Once the insurgents who disrupted entire industries – dethroning IBM, Nokia, Sony, and Yahoo – the tables have turned, and they must now confront a harder truth: surviving the next technological revolution will require dismantling parts of their own success.

Meanwhile, a new generation of startups is showing what real reinvention looks like. Their AI-native architectures offer a glimpse into a future where digital environments are dynamic, interconnected, and constantly evolving to meet user needs.

Just as the personal computer and the internet once reshaped the corporate landscape, AI will demand not just new tools but new organisational blueprints. Those who cling to old structures in the face of systemic change are not overtaken by chance – they are overtaken by design. AI will not simply reward early adopters; it will reward bold architects. For investors, this means looking beyond product rollouts to assess which companies are redesigning the foundations of how they operate, and which are merely reshuffling the surface. Whether today's tech empires will have the courage to adapt – or whether they, too, will be remembered as relics of a previous age – remains to be seen.

1 https://medium.com/@sanwar/the-unseen-pattern-in-kodaks-decisions-60220212c5b8

2 https://www.adweek.com/media/google-ai-search-ad-business-openai-perplexity/

Emanuel Whybourne & Loehr Pty Ltd (ACN 643 542 590) is a Corporate Authorised Representative of EWL PRIVATE WEALTH PTY LTD (ABN: 92 657 938 102/AFS Licence 540185).Unless expressly stated otherwise, any advice included in this email is general advice only and has been prepared without considering your investment objectives or financial situation.

There has been an increase in the number and sophistication of criminal cyber fraud attempts. Please telephone your contact person at our office (on a separately verified number) if you are concerned about the authenticity of any communication you receive from us. It is especially important that you do so to verify details recorded in any electronic communication (text or email) from us requesting that you pay, transfer or deposit money, including changes to bank account details. We will never contact you by electronic communication alone to tell you of a change to your payment details.

This email transmission including any attachments is only intended for the addressees and may contain confidential information. We do not represent or warrant that the integrity of this email transmission has been maintained. If you have received this email transmission in error, please immediately advise the sender by return email and then delete the email transmission and any copies of it from your system. Our privacy policy sets out how we handle personal information and can be obtained from our website.

The information in this podcast series is for general financial educational purposes only, should not be considered financial advice and is only intended for wholesale clients. That means the information does not consider your objectives, financial situation or needs. You should consider if the information is appropriate for you and your needs. You should always consult your trusted licensed professional adviser before making any investment decision.

Emanuel Whybourne & Loehr Pty Ltd (ACN 643 542 590) is a Corporate Authorised Representative of EWL PRIVATE WEALTH PTY LTD (ABN: 92 657 938 102/AFS Licence 540185).Unless expressly stated otherwise, any advice included in this email is general advice only and has been prepared without considering your investment objectives or financial situation.

There has been an increase in the number and sophistication of criminal cyber fraud attempts. Please telephone your contact person at our office (on a separately verified number) if you are concerned about the authenticity of any communication you receive from us. It is especially important that you do so to verify details recorded in any electronic communication (text or email) from us requesting that you pay, transfer or deposit money, including changes to bank account details. We will never contact you by electronic communication alone to tell you of a change to your payment details.

This email transmission including any attachments is only intended for the addressees and may contain confidential information. We do not represent or warrant that the integrity of this email transmission has been maintained. If you have received this email transmission in error, please immediately advise the sender by return email and then delete the email transmission and any copies of it from your system. Our privacy policy sets out how we handle personal information and can be obtained from our website.

NewsLetter

Free Download